My grandfather was a medical doctor, a physician. By following the Hippocratic oath he gave years ago, he still is one, even though he has been retired for more than 15 years now. The only kind of medical work he practices these days are regular health checkups for commoners in his birthplace village in the midst of a mountain range in northwestern Bosnia. Being an MD, he is regarded as a local deity of sorts. He comes and goes from time to time, checks local villagers’ blood pressure, dresses ax wounds, cleans and stitches up deep cuts, and shares advice to keep the local community healthy. I guess that kind of activity keeps his existential sense of meaning alive and well.

This grandfather of mine was utterly confused when he learned that I had quit my job and started my company. Though he didn’t fully understand what my previous job was, he knew I was a director, and to him, that was quite enough. If anyone asked, he could explain very quickly what I did. “He is a director in an international company,” he would say. Titles meant everything in the Yugoslav socialist system he grew up in.

Quite naturally, he was unable to process the concept that anyone would want to quit being a director, let alone to start a private business.

Worried for my newly established family (and my mental health), he repeatedly asked why I had done such a thing and what is it that I do these days other than staring at the computer screen for long hours up in the attic. Every time I attempted to explain what I do, I failed miserably as soon as I started talking about human capital. He would mumble and shrug it off and ask if I earn enough money to put food on the table for his great-grandchild.

A similar thing happened when my little brother tried to explain that he was studying computer science. Though Grandpa would show genuine interest in learning for the first 20 seconds, by the end of the 30th second, he would grumpily give up and retort something along the lines of “That’s all Chinese to me.”

I appreciated my grandfather’s interest. He was genuinely curious to learn, but I kept failing with my explanations. At times I would manage to reach that 30th second keeping his full attention, and then I would say something like “due diligence” and immediately fall into quicksand. The harder I tried to get out of the trap I’d put my explanation into, the less amused my grandfather’s face would become. “Well, ok, as long as you are happy and earn enough money, that’s fine,” he would say after a short break and a sigh.

His lack of understanding started to seriously bother me. It became an obsession. A challenge. I knew grandpa was keen on learning about what I do, and I was determined to find a proper way of explaining what my company is all about to my MD grandpa… MD grandpa. And that’s when the light bulb went on.

“Ok, Grandpa, you were a doctor…”

“I am a doctor,” he stopped me in my tracks. “I studied under Professor ‘X,’ who was the best surgeon in the whole…”

“Ok,” I continued. “Let me try to explain what I do in an allegory I believe you will be able to understand…

The human body is a system. The basic building units of that system are cells that bind into tissues, that bind into organs, that bind into organ systems that comprise our whole body. If something goes wrong with any of these building units or if the interaction between these subsystems doesn’t work, our organism experiences an illness or a disease that prevents us from thriving.” I managed to capture my grandfather’s attention.

“Organizations such as private or government-run companies are systems similar to living organisms. The basic building units of that system are employees that bind into teams, that bind into departments, that bind into divisions that comprise the whole company. If something goes wrong with any of these building units or if the interactions between the subsystems don’t work, the system experiences an illness, a disease of sorts, that prevents it from thriving.

Physicians use diagnostic tools such as blood tests or blood pressure monitoring, X-ray, MRI and PET scans, or even genome analysis to determine whether there is something wrong with your body, whether you are ill or susceptible to becoming ill.

Similar to a blood test or blood pressure monitoring, my company combines a set of methods and tools that can help determine whether organization system went awry—whether an organization is ill or susceptible to becoming sick.”

“So, what you’re saying is that you are a doctor for organizations?” Grandpa asked.

This was the first time we’d gotten to questions, so it got me excited.

“I am more like an internet hospital for organizations,” I responded. “I let the organizations come to me, and after an initial screening, I help them diagnose and treat their illness. If they are not sick, I tell them they are doing a good job and what good practices they should continue using, help them share those results with the world, and schedule a regular health checkup… If needed, my hospital connects my patients with specialist doctors who can help with specific requests. However, especially at this early stage, sometimes I play the role of a doctor as well, yes.”

“Ok, but how does that diagnosis look?” – Grandpa asked again.

“You know how the blood test gives you all those results about leukocyte and erythrocyte levels, hemoglobin, etc., but it also gives you reference intervals and flags for each individual result?”

“Yes!”

“Well, my reports are similar to that. I break down the results by common indicators of organizational health and provide information about reference values and flags. After receiving the results, companies can decide whether they will act independently or use the help I can provide them. To relate that to medical practice—upon seeing that your bad cholesterol levels are high, you might design your meal or exercise plan on your own, but you can also consult a nutritionist and a trainer to help you with that.”

“I see. I never thought organizations could get sick. It’s a brave new world out there, I tell you… So… my grandson cures organizations.”

That ended up sounding a bit pretentious, but I considered it a success. It certainly felt like one.

“It’s not rocket science. It’s social science.”

The title of this blog post is “What to do if and when your organization falls ill.” So, now that I have used the long introduction to share my metaphor, I will continue the post with a question and an answer: what is the first thing you normally do when you fall ill?

Usually, you have two options—you either self-diagnose (because you have seen a doctor so many times that you know what symptoms you are experiencing and you know just the right remedy), or you go to your physician to ask what is wrong with you and how to fix it. The first thing the physician will do in this case is to engage in a diagnostic process to learn how to help you.

Unlike medical diagnosis, which is based on the laws of natural sciences, organizational diagnosis has its origin in theories and methods derived from social sciences, such as industrial/organizational psychology, economics, sociology, and anthropology. To conduct a complete human or intellectual capital diagnosis, we take social science research principles and theories and apply them to our business setup.

We hear a lot these days about people (or HR) analytics practice. People analytics are nothing more than social science research methods applied in a commercial setup. Not all people analytics are human capital diagnostics, but all human capital diagnostics are essentially people analytics practices.

As in any diagnostic process (whether medical, organizational, or any other), knowing how to categorize symptoms and getting the proper information—getting diagnostically valid data—from the “patient” is critical.

Three primary “senses” are used for input collection in human capital diagnostics: employee-company transactional data inspection/collection, survey feedback, and live interpersonal interviewing/participant observation audit. Recently, there has been a breakthrough in wearable device data collection methods. These data generating tools are sturdy and very insightful but also a subject of controversy and broader ethics polemics.

No matter what type of methods you use to collect inputs, to gain some meaningful information out of the data you have received, you need to have a theoretical framework to peg your numbers and observations and back the reasoning behind the collection.

In my experience, companies tend to hoard employee-related information without a framework in mind. “We will take this data and see how it goes…” or “Why not collect that piece of information as well?” are the kinds of sentences you can hear from analytics teams around the globe. Often, they have piles of data that are unstructured and lack systems to the point that it is entirely useless. The data fetishism is becoming increasingly prominent in the digital era because of the ease of information collection. Data is everywhere around us, and we just can’t help ourselves; we snatch it and turn it into beautiful graphs that tell us everything about absolutely nothing.

To conduct a proper human capital diagnostic process, you need to know exactly what kind of data you ought to get before the collection starts. You’ll know what kind of data you’ll need for the analysis only once you have a theory in mind. You can either have a hypothesis you would like to test or follow an existing paradigm that has been validated through years of studies and published in peer-reviewed journals to get a meaningful result out of your research.

Yale professor Dr. Clayton Alderfer, who wrote at great length about organizational diagnostics, explained in four key points the primary objectives of a theory:

- Theories define what phenomena are to be examined.

- Theories explain phenomena in their domain.

- Theories predict phenomena in their domain.

- Theories allow people who are knowledgeable enough to work with and influence phenomena in the theory’s domain.

Utilization of existing diagnostic paradigms and theories can help you leverage years of research and benchmarking data to grasp how behavioral components of your organization can be explained and predicted.

Orgnostic’s approach

The diagnostic framework developed by Orgnostic is governed by contemporary theories from leading researchers in industrial psychology. We anchor our diagnostic structure in the work of the late Harvard professor J. Richard Hackman that examines a team as a central organizational building unit and explores the essential and enabling conditions needed for a team to be efficient and productive.

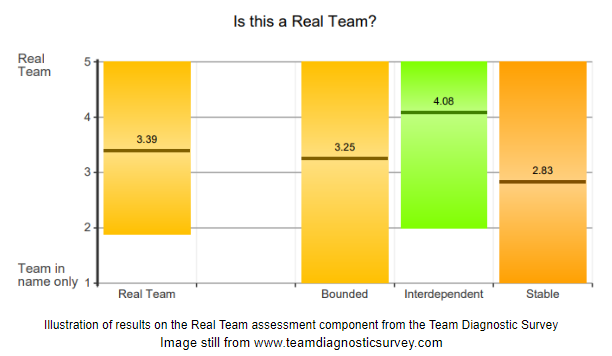

To conduct a diagnosis, we look at whether the team is a real team or a team in name only, whether the team has the right blend of competencies and skills to achieve its work, and whether the members are working toward a compelling purpose. On top of that, we examine whether the team size, tasks, and norms benchmark with the optimal structures, whether the organizational context supports team actions, and whether the members have access to expert coaching from within or outside the organization.

Depending on the size, maturity, and strategic goals of a company, we zoom in and away from the team as a crucial building block of the system and stack complementary theories to assess the interactions within the organizational system by examining the leadership capital, culture, values, engagement, burn-out risk, well-being, quality of processes, performance accountability, rewards efficiency, and in/out talent management practices.

Our partnership with academia is the key to creating authentic value for our customers by utilizing leading researchers’ years of experience and validation of their theoretical frameworks across multiple industries and areas of study.

The results of the diagnostic process could serve multiple purposes. Nonetheless, Orgnostic indices are used in two prominent ways—by HR leaders and organizational leadership for human capital strategy design and by investors (VCs and PEs) for prospect assessment in a due diligence process.

The end result of the diagnostic process is a numerical dashboard that is used as a quantitative KPI baseline for the HR and leadership team. Upon reruns of the process and pulse checks in the six-month to one-year period, company leadership can track how their changes in management practices have improved the index score.

Even if the organization is completely healthy and there is no area for improvement in management practices, which is rarely the case, having the right theoretical framework to govern the best practices and the tool to make sure you stay healthy is always a good choice.

You know what they say—an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

References

Leading Teams: Setting the Stage for Great Performances, J. Richard Hackman

The Practice of Organizational Diagnosis, Clayton P. Alderfer

If you share our vision for the future of human capital management, get in touch with our team.