It was a cold November night in Vancouver some four years ago. I was snuggled in a cozy AirBnB apartment in Yaletown, together with my new acoustic guitar, which I had bought on a pretty good Black Friday deal. Since I had started working my new job, which required me to travel extensively, my commitment to the art of music and my performance skills had waned. Picking up the guitar that night, I was determined to learn a new song, one that YouTube’s conjuring algorithm had reminded me of just hours before.

(For those interested, here is the link to the song, Drifting by Andy McKee. It makes an excellent soundtrack for this read.)

That night, I entered “the zone,” the experience Mr. World Peace so eloquently talks about in his lyrical masterpiece. I was fully immersed in the instrument and the task of conquering the song. I completely lost track of time and felt deep fulfilment upon reaching the goal. It was marvelous.

I experienced this feeling many times in sports and music, though I took it for granted prior to my career. Due to the two-year hiatus between the two experiences, I was no longer taking the “in the zone” feeling lightly.

My main concern was – why wasn’t I getting into that state while doing my regular job?

A few months passed since that night in Vancouver, before I decided to learn to code. I wasn’t keen on becoming a developer, but I wanted to become technically literate and better understand the tech community I was a part of.

So, I started light by taking one of the classes on EdX. A few weeks into the program, our class was tasked with creating a simple video game. I was very keen to develop a program that would do something. As I was coding, I got stuck multiple times and struggled to figure out how to get my little character to move horizontally around the plane. I engaged in a trial-and-error cycle with a clear vision of what the game was supposed to look like. Code, test, fail, revise, test, succeed, code, test…I suddenly realized it was 4 AM and that I didn’t even care that I had to do some interviews in just a few hours.

I was once again zoning and experiencing an overwhelming enjoyment.

After I concluded the interviews and meetings and managed to reflect, I was at once awestruck and envious of how easy it is for developers to get in the zone.

Why was I not able to get into that groove at my job? I was pleased with my work – I loved it – but I had never spontaneously reached this state of hyper-focus.

Experiencing a mild professional crisis, I wondered whether it was the passion for the field that was the differentiator between the usual chaotic state of mind and the superior state of hyper-focus?

I easily dismissed this hypothesis, however, as I wasn’t particularly passionate about programming.

This day marked the definite start to my inquiries into the psychology of “being in the zone.”

I didn’t doubt there would be tons of written material, as well as videos and podcasts, about this state of mind.

In the field of positive psychology, it is known as the state of flow or the state of optimal experience. The concept was christened and pioneered by professor Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, a Hungarian-American born in Rijeka, a piece of trivia my Croatian readers and friends might appreciate. (Also, this is a nice opportunity to thank Larry Tesler for inventing copy/paste function, without which I would not be able to present Mihaly’s last name accurately; so as to not abuse the c/p function, I will refer to the professor as Mihaly C. for the remainder of the text).

(The link to a TED talk by Mihaly C. for people wanting to learn more.)

I found the concept of flow to be fascinating, completely matching my two previously described recollections: “involvement in what you were doing that the rest of the world seemed to have disappeared; your mind wasn’t wandering; you were totally focused and concentrated on that activity, to such an extent that you were not even aware of yourself.” Most of the accounts surrounding this kind of experience came from people who make music, dance, sail, play chess, or rock climb.

In theory, six factors indicate the experience of flow:

- Intense and focused concentration on the present moment;

- Merging of action and awareness – activities become automatic and involvement effortless;

- A loss of reflective self-consciousness – perception of existence is defined through the sole activity on which you are focused;

- A sense of personal control or agency over the situation or action;

- A distortion of temporal experience, one’s subjective experience of time is altered – hence the feeling of slowing or acceleration of time;

- Experience of the activity as intrinsically rewarding (also referred to as autotelic experience) – it has a purpose in itself, meaning that the action is done for the sake of the action and not with any other ends in mind.

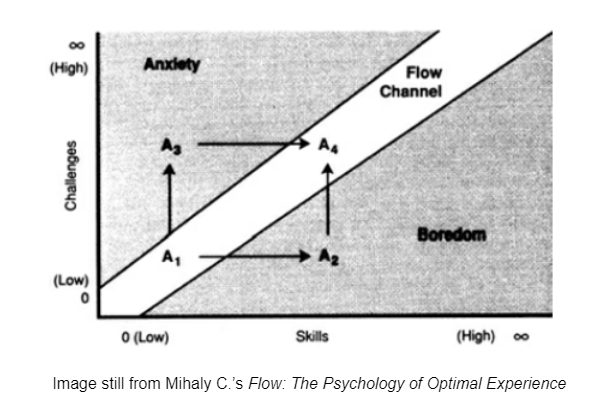

Through his years of research, Mihaly C. concluded that a few external factors need to align for one to reach the state of flow. There are three primary conditions for getting there:

- Clarity of goals – you need to have a perfect understanding of what you ought to achieve;

- Challenging task – the task needs to be at an adequate skill level, which means it must be neither too challenging nor too easy. If the job you are working on is way above your skill level, it causes anxiety; if the task is too easy, it causes boredom.

- Immediate feedback – you need to know right away what you are doing well and not well and have a chance to fix it along the way, without breaking the state.

The research made clear that some professions are more prone to getting to this state of mind. It was amusing to find that the list of people citing accounts of quickly reaching the state of flow was absolutely deficient in office-bound professionals.

Returning to my learning how to play the song “Drifting,” it is evident how conditions aligned: I had a clear goal – to learn how to play that song; the task was challenging, so it was stretching my abilities and skills along the way; and I got instant feedback – every time I played a wrong note, I was able to hear it and make adjustments through repetition.

We can draw a parallel between music and programming – developers, too, are able to quickly get the feedback on their work – although, the feedback when you code is not instantaneous, it is almost effortless to check whether a line of code produces the desired output or not. You can quickly revise that line and test again and again and again until you get it right.

Software engineers are one of the professions that reach this state without organizational interventions, but what about other company functions? What about business development, operations, marketing, finance? What about HR?

HR professionals might have the hardest path, out of all professions, to “the zone.” A typical HR job requires constant multitasking and content switching between talent acquisition, stakeholder management, change processes, employee support, administration, etc. Guru of HR, Dave Ulrich cited one of the critical competencies of HR to be a “paradox navigator.” How is it possible for a person who is supposed to be a paradox navigator in the organization to reach a state of hyper-focus on anything?

On an average day, your goals are contradictory; your focus is scattered across the organization; your skills need to be T-shaped so you can cover ground; and the feedback is – let’s face it – quite scarce, as some of the things you are working on only produce results weeks, months, or years from now. Plus, your colleagues are not always that honest.

I started imagining an organization and a nudge system that could maximize the flow opportunity for different job roles. I was determined to challenge an average HR role and turn it into an experience that reaches beyond its traditional function. The aim was to make the average HR job a happier experience.

Here are my four recipes you can implement in your job and your organization to help yourself and others optimize the chances of reaching the flow:

Eliminate distractors

An open office setup carries loads of distractors that can prevent you from keeping your mind in the zone. Be it the people just passing by from and to a lunch break and being polite by saying hi, to the ones who are bored and want entertainment for a bit. Also, expectations that every email and chat must be answered in a few short minutes don’t help either.

A couple of things you can do to avoid these scenarios is to create/dedicate “focus booths” – places where people can work in private without being constantly interrupted. Once in these rooms, you can use one of many cool apps to block your access to social media and other web distractors that prevent you from achieving the state of focus.

If you are a policymaker in the company, you can reduce the number of distractors in your workplace through an email/chat app amnesty agreement, which sets expectations about response times and limits the number of hours dedicated to chat or email communication.

A little extra: the pomodoro technique is a great way to start your flow training process.

Define goals and break them down into small chunks

Video gamers are amongst the population that almost infallibly reaches the state of flow. Being in the zone is what makes playing video games so enjoyable. For the gaming experience combines perfectly all three conditions needed to achieve the state of flow, as one of the most prominent features of video games is very clear goals that are broken down into small chunks.

In a workplace, your goals are seldom so perfectly broken down. In many cases, you need to do some work to figure out the final goals of your endeavor. In other scenarios, goals are very vague, and the path towards achieving them can become quite winding, to the point that you can get lost often. Invest time in crafting your work experience to mimic a video game as much as you can – gamify!

Figure out what your final goal is, the big hairy audacious one, and start breaking it down into smaller milestones, as small as daily milestone lists. Make sure you grant yourself a reward upon completion of your group of milestones, or individual goals. (Sometimes, for the individual goal, the conclusion will be enough of a reward in itself, since the feeling of scratching things off the list can be quite strangely satisfactory).

If you are a policymaker, encourage the goal of setting practices in the office by introducing performance frameworks that encourage short goal-setting cycles (agile methods and OKR systems are quite compatible with this idea). Here is a link to a text by Neil Patel to help you understand gamification principles better, and another link to a number of cool gamification practices that can inspire you.

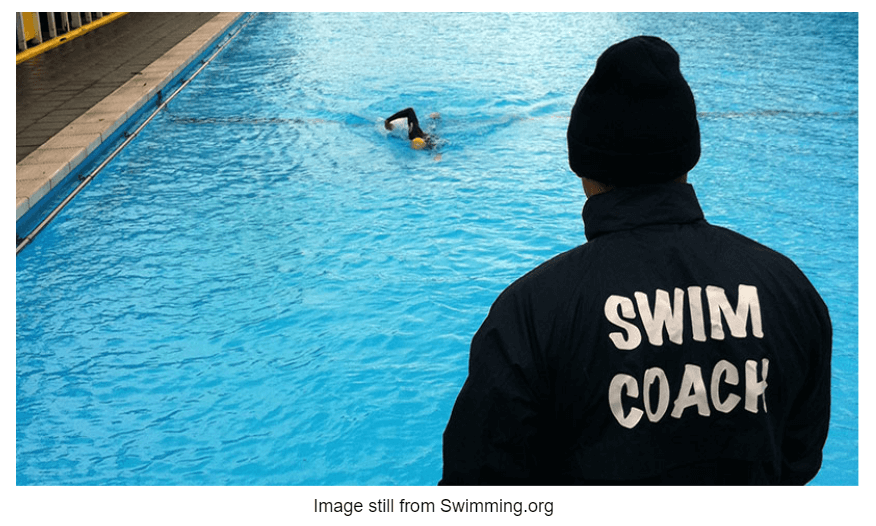

Design tasks so they stretch your abilities

Athletes are another category of people who reach states of flow without thinking about it too much. One of the main reasons is that they are continually being pushed slightly out of their comfort zone. Every other training session is about stretching athletes’ ability just a bit; the goal is to go a small step farther than the last time around. With each training cycle, they build their skills and abilities and continue pushing to new levels. While some athletes are so disciplined that they can continuously stretch themselves in practice, it is usually the role of the coach to be the person who pushes them over the edge.

A couple of things you can do to empower this behavior in your organization is to train your leadership in the ways of athletic coaches. If you are a leader, consult with your L&D team to define the gradation of skills for different jobs. Also talk to your employees to test how confident they feel about their skills and capabilities to solve the challenges ahead.

One more thing you can do is to design tasks in such a way that they are to be done in pairs, where one person has just enough skill to complete the work, while the other is a step below. This way, they will motivate each other to do their best, with one person establishing the command over the skill level, and other stretching to the new heights.

Be careful with this step, as stretching too much can cause frustration that can eventually lead to burnout.

Create feedback loops

One of many great things about playing music is that your performance produces instant feedback. You are aware you made a mistake every time you do so. For example, when you are trying to play a favorite tune, you are conscious of the result you want to reach, and there is no need for anyone else to tell you that you played a wrong note. Moreover, you can repeat the process every time you make a mistake until you get the desired tune right. Not every job grants you this kind of perpetual feedback. In posts like HR, you need to make an extra effort to create your feedback loops.

Once you introduce goals and break them into small chunks, make sure to determine the key results you want to reach. Be very precise in determining your results and visualizing what success means. Once you’ve done that, make sure you set some measurable elements that are easy to track, so you can check on your progress as you reach your milestones. You can start by transforming your end of the day reports, or task lists, into batches of goals with measurable outcomes. Once you have determined your measurable daily feats, try beating them the next time around.

One of the solutions I unintentionally provided by creating the Orgnostic platform is the ability to create various feedback loops for your HR team by setting measurable goals that accompany your initiatives. While the feedback generated with Orgnostic is far from immediate, it does provide a numerical meta overview of your project success and serve “big goal” metrics.

The work done by positive psychologists on topics of eudaimonia, including the works of Mihaly C., Martin Seligman, Dan Gilbert, and all-time greats such as Albert Bandura and Carl Rogers, is no less than heartening.

The thought that you don’t need to be an artist to achieve an artist’s state of mind is inspiring. Knowing the secrets to zoning, or reaching the state of flow, helps to awake an artist’s experience in any profession.

In this blog entry, I shared a couple of simple ideas about the things you can do in your everyday job to embellish your experience and feel happier at work. Being in a position to change the way our organizations work towards more productive and enjoyable environments brings a responsibility to do what’s in our power to enhance our employee’s experiences, as well as our own.

I encourage all of you to test these recipes and to enhance them with your own approach, all with the goal of making our workplaces more similar to art studios.

Help yourself and others design their pursuits of happiness.

References:

Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. Flow (Harper Perennial Modern Classics) HarperCollins e-books.

If you share our vision for the future of human capital management, get in touch with our team.