Just a couple of months back, in October 2018, The World Bank published a set of new measurements of overall national health and well-being gathered under the umbrella of the so-called Human Capital Index (HCI). The published research is part of the World Bank’s global initiative called the Human Capital Project, aka the Project for the World, which aims at emphasizing the urgency and critical importance of investing in people to prepare nations for the economy of the future.

The HCI, in its bare essence, provides a glimpse into three key variables—survival, education, and health—for every country on Earth. Based on these variables, it measures the value of the next generation of a country’s human capital; that is, a country’s capacity to be productive, innovative, and flexible in the years to come.

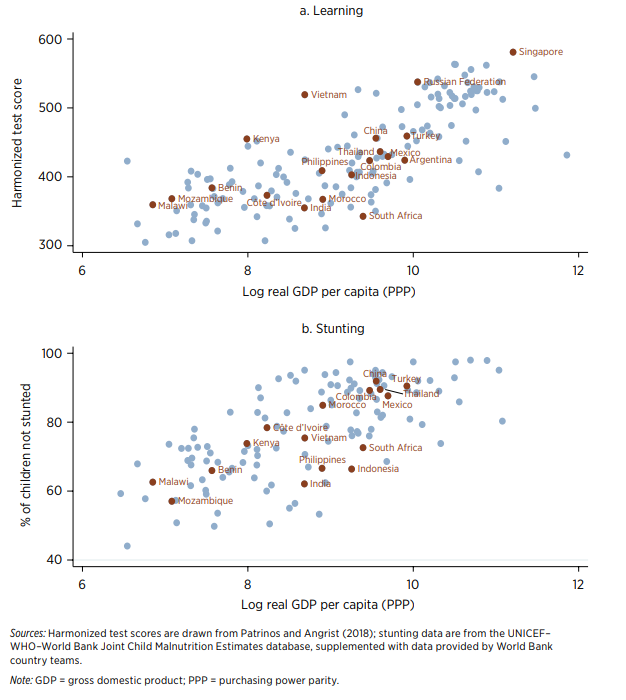

Each country receives an index score between zero and one based on the sum of the individual variable indices. Interestingly enough, the World Bank’s researchers established a direct correlation between HCI and GDP—a country that scores 0.5 on the HCI has an opportunity to double its GDP per worker if the government reached the highest benchmark of health and education. In comparing its score to GDP, which can be looked at as an output measurement of human capital, HCI’s purpose is to assess a country’s potential and predict its future output.

While it is an ambitious and far-reaching project that should eventually help governments create a better world for the children of the future, I found the project’s results extremely interesting for their implications for the future of human resources departments, as a subset of a broader category of human capital curators. It brought to light at least three major facets of the current state of work and workplaces:

- Business and industry are always changing;

- Investment in the betterment of human capital is the key to the world’s future success; and

- Our outdated output measurement tools require improvement, which can be achieved by the addition of “leading” metrics, or parameters that can better predict events, on the basis of which we can act.

Each of these axioms contains a piece of the puzzle to solving the challenge of positioning HR as the vital strategy driver for businesses in the new economy. I will dive deeper in addressing all three.

Knowledge workplace

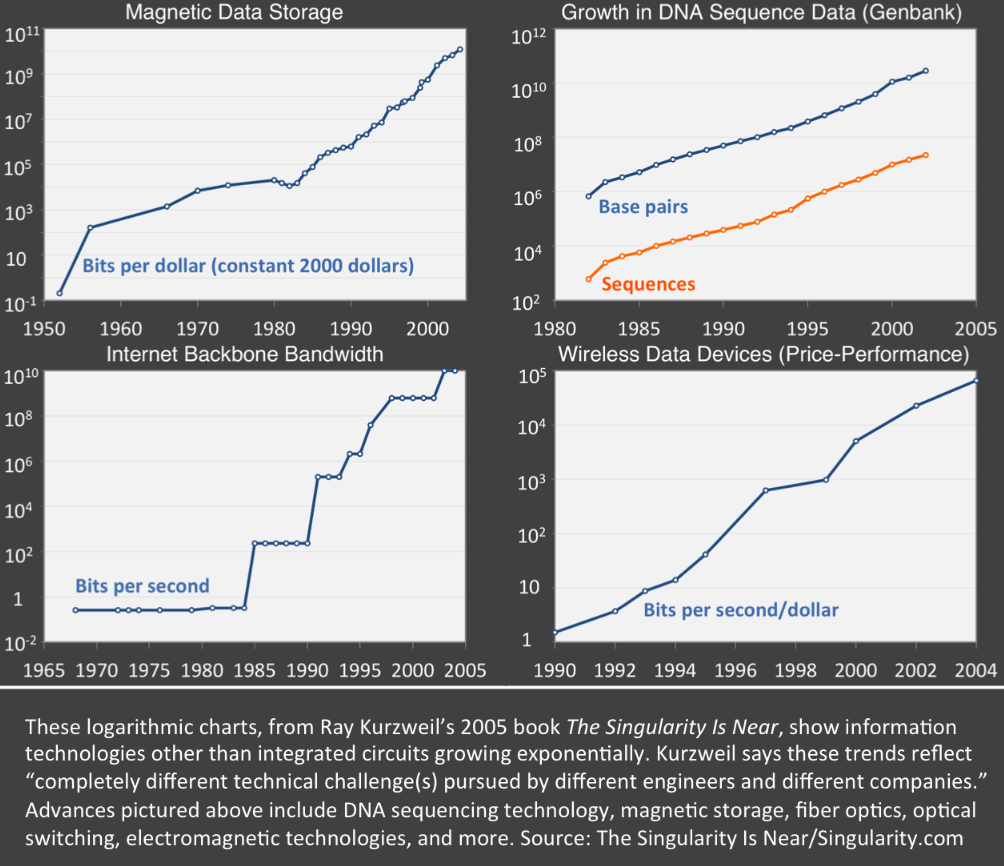

Technology is changing business. There’s nothing groundbreaking about that statement—this has been true since the dawn of the first industrial revolution, and we are now on the brink of the fourth. However, the pace of technological evolution has never been as fast as it is today (if you question that statement, please read Kurzweil’s The Singularity is Near).

As a response to the fast and furious pace of industrial change, companies and their organizational systems are learning ways to adapt. As with every evolutionary process, mechanisms of natural selection are powering this process of change—organisms (in this case businesses) that do not adapt die out. One of the ways to survive is to appropriate the methods of the newer, more successful species in any new, given context. At present, that new species is the tech startup—what this new breed of company does particularly well in order to stay alive and relevant is innovate.

McKinsey revealed that innovation as a critical strategic imperative is gaining a great deal of traction among company executives and is quickly sneaking into boardrooms across the globe. Innovation is now one of the top strategic priorities for any organization that is battling to survive in this fast-moving and competitive marketplace. The reality of all this has caused a significant shift in what companies need from their workforce—not task workers but knowledge workers, i.e., workers who aren’t engaged in repetitive work but instead whose key asset is using their knowledge and ability to improve processes.

Knowledge workers, however, require knowledge workplaces.

Gartner defines a knowledge workplace as “the intersection of three key trends: the leverage of intellectual capital, the virtualization of the workplace and the shift from hierarchical to organic models of management. The focus is on knowledge as the primary source of competitive advantage.”

The fact of the matter is, we are still actively learning how to leverage intellectual capital, what it means to virtualize the workplace, and how to be organic managers. We struggle to manage the new context.

One of the fundamental principles of management as described by Peter Drucker is that if you can’t measure something you can’t improve it. Learning how to measure and assess knowledge workplaces will give us the edge in managing them. This new learning is a unique opportunity for positioning HR as the critical driver of business value.

The value of intangibles

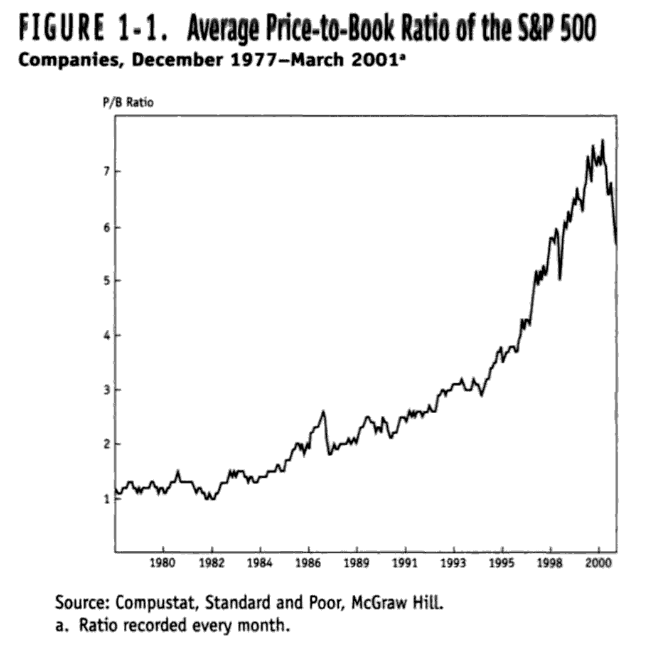

Even though the workplace has evolved, the way we evaluate its success and effectiveness has remained somewhat stagnant. There is a widening gap between the way experts traditionally assign value to our businesses and the way the market does it.

The gap is easy to see in the book to market ratio trends among S&P500 companies since the ‘80s. NYU professor of accounting and finance, Baruch Lev, identified this trend some 18 years ago when the market value of companies was peaking at more than six times their book value!

In a recent interview, Professor Lev stated that a company’s ability to innovate and be relevant in the future is determined by the ideas, processes, and abilities of their employees and leadership, things that should dictate the value of a company more than its current financial performance.Today, almost 20 years after this research was first published, intangible assets account for more than 80% of the value of S&P500 companies. Intangible assets include brand value, patents, copyrights, and R&D, but also organizational and human capital. According to Professor Lev, intangibles are any knowledge-based asset that promises future benefits. In knowledge workplaces, these assets are ideas, processes, and employees.

Still, we don’t seem to find measurements of the value of human capital relevant when it comes to choosing business strategies and tactics. Why is this the case?

I believe one part of the answer is that people who deal with business valuation and business strategy are usually not trained in industrial and organizational psychology. The other part of the answer might be that people who deal with human resources are generally not taught the ways of business and finance.

How do we measure what is intangible?

The most plausible reason why human capital measurements are not getting the attention they deserve is that measuring intangibles is not easy and not as straightforward as measuring financial outputs. Still, there are various methods of capturing the value of employee-related intangibles that I/O psychology researchers and other organizational experts use in organizational diagnostics.

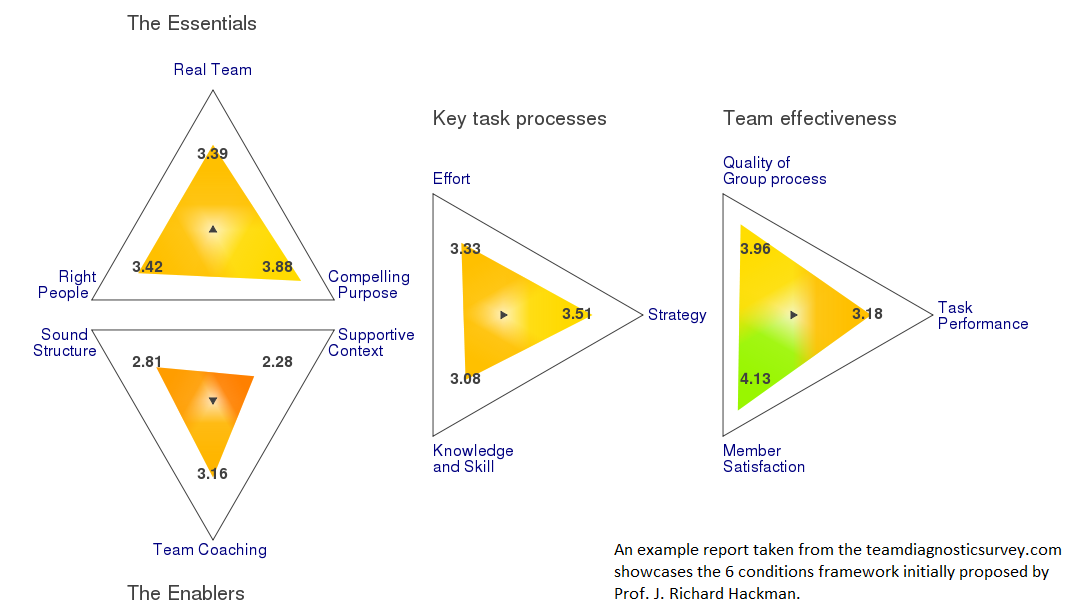

During my college days, I had the privilege of studying under and working with the late Professor J. Richard Hackman of the Harvard Psychology Department and Harvard Business School. He dedicated his career to researching what distinguished high performing teams from average and low performing ones. He came up with the framework of six conditions for team effectiveness: three essential factors (having a real team, a compelling direction, and the right people) and three enabling factors (building a sound structure and a supportive context, and the ability to access expert coaching). Meeting these conditions leads to increased team performance. Units in which leadership got the conditions right were more likely to be stable and better performing in the future. Hackman developed a tool called the Team Diagnostic Survey that helps measure and assess whether the conditions are in place.

More recently, Dave Ulrich, an HR guru and the father of modern HR, published a book titled Leadership Capital Index, in which he explored ways of evaluating a company’s leadership potential and turning it into a tangible metric that investors can use for benchmarking purposes.

These are just some of the examples of positive diagnostic practices that create reliable, benchmarkable, and actionable items that HR directors and organizational leadership can turn into a framework for company strategy and tactics leading to efficient human capital management in a knowledge workplace. These examples of leading metrics are the kinds of new KPIs HR can apply to their practices so that they can drive future business value.

The need for a new human capital metrics framework

Many organizational diagnostic practices exist independently one from another. Currently, there is no single framework leaders can use to conduct a complete organizational due diligence of a company and get the right set of measurements for designing a human capital management strategy that will be an essential part of an organization’s business strategy. I felt that first hand when I was in a position to lead a global People Operations function in an international IT company.

The company I started, Orgnostic, is on a mission to create an ecosystem in which intangible measurements of human capital can serve organizational leaders, HR directors, investors, and other corporate influencers who want to change the way they assess the value of human capital and then revise, improve, and establish new strategies for HR and organizational development.

Not unlike the World Bank’s Human Capital Project, Orgnostic has the vision to index the value of organizational human capital and use it to create better work systems and workplaces around the globe. Orgnostic builds and organizes measurements of knowledge workplaces in order to improve the world’s management practices and create healthier work environments.

References:

The Human Capital Project, World Bank